Strange Days or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Lore

J. Kennedy is back with another fabled edition of his singular series

Strange Days or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Lore

Words by James Kennedy

Strange Days screens at Cinema Nova this week.

March 7, 2010

The 82nd Academy Awards

Hollywood, California

Over 41 million viewers watched live as the film industry staged one of its most symbolically loaded ceremonies in decades. The Oscars that night were supposed to be a celebration of cinema in 2009, but the narrative dominating both industry trade press and broader media coverage had very little to do with the year’s best films. Instead, it centred on a rivalry between two former spouses: Kathryn Bigelow and James Cameron.

Both directors arrived at the ceremony with nine nominations apiece, Bigelow for The Hurt Locker, a spare and suspenseful portrayal of American soldiers dismantling IEDs in Iraq; Cameron for Avatar, a visually monumental science-fiction epic that had already shattered box office records and was rapidly becoming the most commercially successful film in history. The contrast between the two films, one shot with handheld cameras in Jordan on a $15 million budget, the other rendered in 3D with motion capture technology and a budget north of $240 million, could hardly have been sharper. That their creators had once shared a marriage only made the optics more irresistible.

Media coverage in the weeks leading up to the ceremony leaned heavily on the “battle of the exes” framing. It was reductive, but effective. Entertainment Weekly ran timelines. The New York Times published side-by-side analyses of their filmographies. More thoughtful pieces noted the irony that The Hurt Locker, a film about the procedural rhythms of male violence, was directed by a woman, while Avatar, a mythically structured tale about blue-skinned environmentalist aliens, was directed by a man who had made his name through militarised blockbuster storytelling. Even the Academy seemed to lean into the narrative: Bigelow and Cameron were seated near one another, with Cameron placed just behind Bigelow, making for an image that would be endlessly replayed when her name was announced, instead of his, as the winner for the Best Director statuette.

When it happened, it was historic. Kathryn Bigelow became the first woman in the Academy’s 82-year history to win the Oscar for Best Director. It was a long-overdue milestone, given that only three other women had ever even been nominated before her: Lina Wertmüller for Seven Beauties (1976), Jane Campion for The Piano (1993), and Sofia Coppola for Lost in Translation (2003). In that same period, over 400 men had been nominated, many of them multiple times. Bigelow also took home Best Picture for The Hurt Locker, while Cameron’s Avatar ultimately claimed just three awards, all in technical categories.

But what made the moment particularly resonant, especially for those who had followed their intertwined careers, was the shared history between the two filmmakers. Their creative and romantic partnership dated back to the early 1990s, culminating in the 1995 release of Strange Days, a film Cameron wrote and executive produced, and Bigelow directed. Though a commercial failure at the time, Strange Days has since become a touchstone of the techno-noir genre and a prescient meditation on voyeurism, memory, and systemic violence in America, issues that both The Hurt Locker and Avatar engage with, in vastly different ways.

In retrospect, the 2010 Oscars represented a kind of divergence point. Cameron, long seen as the king of spectacle-driven cinema, found his work eclipsed not by a competing blockbuster, but by something intimate, and politically ambiguous. Bigelow, whose work had often been underestimated or mischaracterised, was finally recognised by the industry, though not without being subjected to the gendered framing that had accompanied her entire career. Interviews around the time revealed her discomfort with being labelled a "female director," a phrase that subtly separated her from the craft itself.

The ceremony, for all its gloss, revealed deep fault lines in how Hollywood recognised ambition, authorship, and gender. It was a public reckoning delivered through private history. And at its centre sat Strange Days, a film that had come and gone with barely a murmur fifteen years earlier, now recast in the minds of many as the ghost that lingered between them.

Filming on Strange Days was originally scheduled to begin on May 12, 1994, but was delayed until June 6 as the final pieces of casting were locked into place. By then, the city of Los Angeles was already holding its breath. Just two days later, on June 12, Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman were murdered in Brentwood, triggering one of the most sensationalised and racially charged criminal investigations in American history. As Kathryn Bigelow rolled cameras on a speculative vision of a fractured, paranoid, surveillance-soaked Los Angeles, the real city was descending into something strangely similar. The O.J. Simpson trial would come to dominate American media, a high-stakes legal theatre pulsing with racial tension, police corruption, and the voyeurism of a country obsessed with its own unraveling.

Strange Days was shot entirely in Los Angeles over an extremely grueling schedule of 77 consecutive nights through the summer and autumn of 1994. The production wasn’t cloistered away on studio lots or distant sound stages, it unfolded directly in the urban spaces the film sought to critique. Bigelow and her crew staged scenes in the subways, the financial district, and Sunset Boulevard. Filming downtown required the kind of logistical manoeuvring typically reserved for political rallies or Olympic parades. At one point, the team received special permission from the West Hollywood film commission to shut down several lanes of traffic on Sunset for two full days, an exceptional allowance granted only to productions with vision and backing in equal measure.

Despite the scale and complexity, producer Steven-Charles Jaffe later recalled that the city was largely cooperative, with the exception of the underground. The subway scenes, he said, allowed for only four hours of access per night, tght parameters that could have derailed most productions. But Bigelow, famously meticulous, came prepared. Scenes that might have taken other directors a week or more to capture were blocked, lit, and wrapped in just a few days. She wasn’t simply directing Strange Days, she was racing against the collapse of the very reality she was mirroring. The O.J. trial had turned Los Angeles into a powder keg of spectacle, scandal, and simmering injustice. And Strange Days, perhaps more than its makers even realised at the time, was capturing its afterimage in real time.

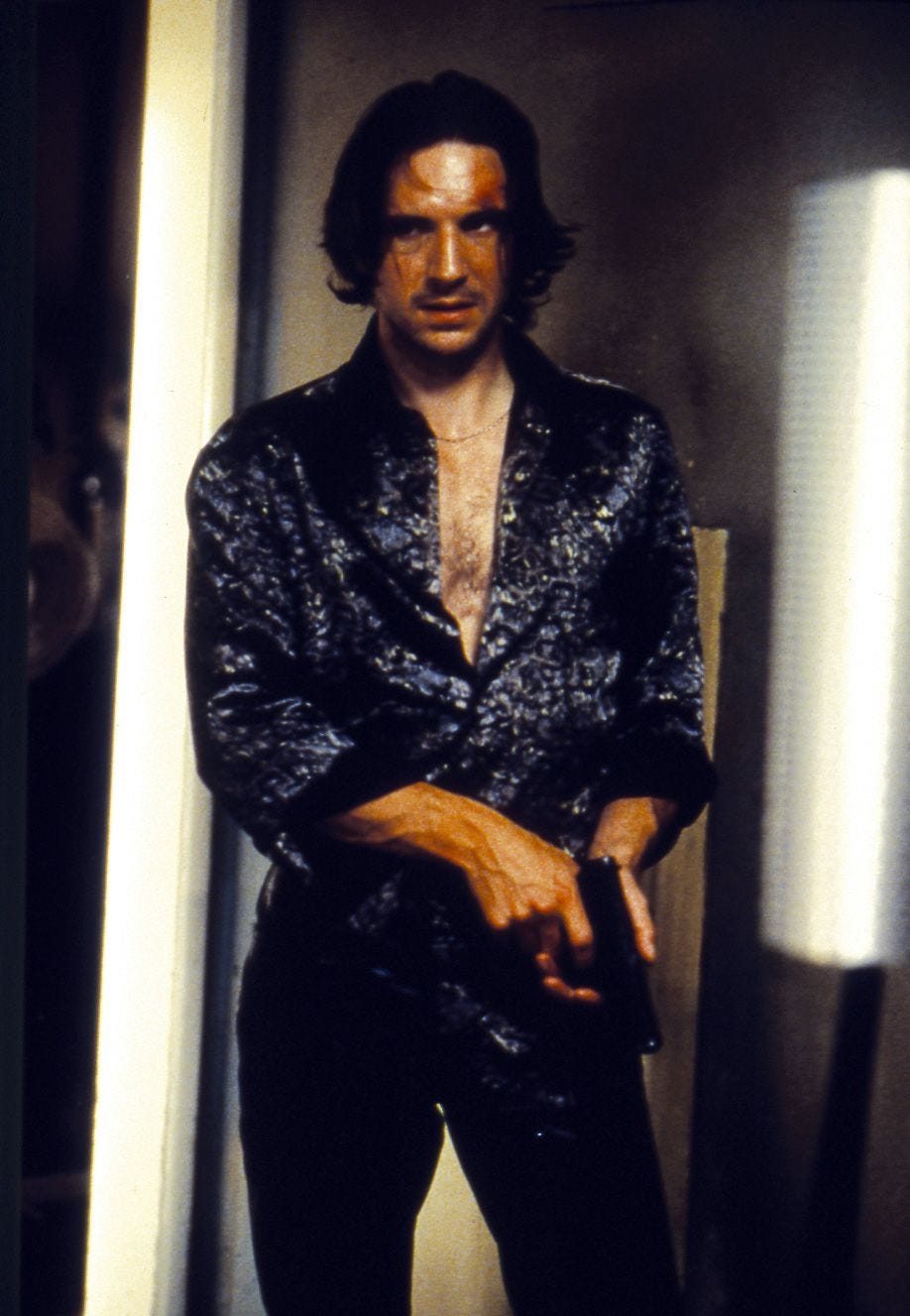

Ralph Fiennes’ wardrobe operates as both armour and artefact. His character, Lenny Nero, a sleazy yet sentimental black-market dealer of VR memories, is perpetually swaddled in oversized, double-breasted suits, often in drapey, charcoal or slate tones that hang off his frame like relics of a better past. These suits, mostly crumpled and ill-fitting, are not the power tailoring of a Wall Street broker but rather the desperate remnants of a man clinging to a vanished self-image. The effect is tragicomic: Fiennes plays Lenny like a former prom king turned street hustler, his dishevelled suiting a costume of denial.

Designed with a 1940s-meets-1990s fusion, the suits recall noir antiheroes and down-on-their-luck detectives, fitting for a character caught in a feedback loop of nostalgia and self-deception. Paired with untucked shirts, greasy hair, and no tie, the look deconstructs the idea of masculine elegance. Costume designer Ellen Mirojnick, known for her work on Basic Instinct and Showgirls, uses Lenny’s clothes as an extension of his psychological disarray. Even when selling illicit experiences, Lenny clings to a code of sentimentality, and his suits reflect that.

Angela Bassett’s portrayal of Lornette “Mace” Mason is the moral and emotional core of Strange Days, grounding the film’s chaos with a performance that radiates both power and restraint. Where other characters spiral in a haze of nostalgia, addiction, or detachment, Mace stands firm, clear-eyed, unsentimental, and immensely physically commanding. Bassett brings a rare mix of vulnerability and authority to the role, becoming the film’s ethical compass, often dragging Lenny back to reality, both literally and figuratively.

Her wardrobe, all-black tactical-wear and sharply cut leather jackets, is as no-nonsense as she is. It’s functional and symbolic armour. The sleek silhouettes emphasise her physicality. But there’s also a radical clarity to her style: in a world obsessed with simulation and spectacle, Mace dresses for truth. In a film thick with excess, of violence, memory, and male ego, Mace’s wardrobe and performance cut through.

One of Strange Days’ most radical contributions to cinema lies not in its plot, but in how it lets us see. The film’s hallmark innovation, the SQUID sequences, which simulate full-sensory recordings experienced from another person’s point of view, required a year of technical development before a single frame could be shot. These scenes, visceral and immersive, are not simply stylistic flourishes. They are the film’s neural core, offering unfiltered access to memory, trauma, and desire as they’re re-experienced through the eyes of another. To achieve this, Bigelow and her team constructed a bespoke camera rig from the ground up: a stripped-down Arri, as she described it, small and light weight but able to accommodate the full range of prime lenses needed to capture clean, dynamic motion.

Cinematographer Matthew F. Leonetti was brought in specifically to execute her SQUID vision sections, which were choreographed in obsessive detail. The opening scene alone, a bank robbery gone wrong, shown in a seemingly unbroken first-person take. Took two years to design and coordinate, involving a 5 metre rooftop jump performed by a stuntman without a harness. That moment alone combines multiple camera systems: a helmet-mounted rig for the leap, a Steadicam for the chase up the stairs, and a series of carefully disguised cuts to stitch it all into a seamless illusion. James Cameron later remarked that the point wasn’t to show off the technical mastery, but to disappear inside it: “We designed transitions that would work seamlessly. It was a very technical scene that doesn’t look technical.”

The climactic New Year’s Eve sequence in Strange Days, where thousands gather in the streets of Los Angeles to celebrate the dawn of the new millennium, is one of the most ambitious set pieces of 1990s cinema. But unlike the usual trickery of film production, this moment wasn’t simulated. It was orchestrated, staged as a real rave in downtown L.A. across multiple blocks at the intersection of 5th and Flower, flanked by the Westin Bonaventure Hotel and the Los Angeles Public Library. Director Kathryn Bigelow, committed to realism at a near-operatic scale, turning fiction into a living event. Over 10,000 extras were recruited. Many of whom believed they were attending a legitimate party, and in many ways, they were.

To conjure the energy of the moment, the production brought in veteran rave promoters Moss Jacobs and Philip Blaine, who were tasked with programming the night like an authentic underground event. The lineup included Deee-Lite and the elusive Aphex Twin, who at the time was ascending to cult status in the electronic scene. Enigmatic and notoriously averse to public performance, he agreed to appear, though he reportedly remained aloof throughout the night. His music, however, carried the mood: layered, dissonant, and unnervingly ecstatic, it formed a sonic parallel to the film’s own collapsing boundary between perception and experience.

The budget for the sequence reportedly exceeded $750,000, with half of the hotel’s 1,300 rooms rented out for cast, crew, and event logistics. The party ran from 9 p.m. and was slated to end at 4 a.m., but was cut short in the early hours due to a string of real-world emergencies. Five attendees were hospitalised for ecstasy overdoses. Witnesses later recalled minor fires sparked by discarded cigarettes, a buildup of ankle-deep confetti, and security systems overwhelmed by the scale of the crowd. More than 50 off-duty LAPD officers were hired for the night, but even they struggled to manage what quickly became a volatile, drug-fuelled mass of people immersed in both a party and a film shoot.

Strange Days is unmistakably filtered through the gaze of a female director operating within, and interrogating, the grammar of the male gaze. Kathryn Bigelow directs not as an outsider trying to reject genre conventions, but as a masterful tactician operating from within them. The film’s sweaty, aggressive, hypermasculine energy, its obsession with surveillance, techno-lust, and voyeuristic violence, is not a byproduct of the genre, but a carefully constructed trap. Bigelow builds a world where male fantasy is currency, and then proceeds to expose it. The SQUID device becomes the perfect metaphor for male entitlement: a technology of possession, one that turns women into experiences to be consumed. But Bigelow doesn’t let the camera, or the audience, off the hook. We are made complicit, and then held to account.

As Strange Days marks its 30th anniversary this year, its dystopian vision no longer reads as speculative fiction, it reads as a blueprint. What once felt like a fever dream of millennial paranoia has hardened into the texture of contemporary life. In 1995, the idea of a militarised police force surveilling and suppressing the most vulnerable citizens of Los Angeles felt hyperbolic, a grim flourish. In 2025, it feels uncomfortably familiar. California is once again under federal scrutiny, this time not for its excesses but for its resistance. The state is being restructured, economically, racially, and legislatively, as the national government exerts increasing control over housing, protest, and human rights. Surveillance technology has evolved beyond anything imagined in Strange Days, yet the emotional apparatus remains the same: fear, spectacle, control. The film’s depiction of state power operating through both brute force and seductive media has never felt closer to the bone.

And so it returns, not just to relevance, but to the screen. Strange Days plays this week at Cinema Nova. A film that never found its audience in its own time, and has long remained unavailable on major streaming platforms outside of The Criterion Channel, where it was added in May 2025. It’s an invitation to witness something once dismissed as overheated or excessive, now revealed to be frighteningly prescient. What Bigelow and Cameron captured three decades ago wasn’t the end of the world, but the beginning of ours.